“No Pressing Need” for a Digital Singapore Dollar Despite Benefits

by Fintech News Singapore November 15, 2021There is “no pressing need” for a retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) in Singapore at this point in time, but market shifts and changing customer expectations are nevertheless forcing the central bank to prepare for a possible issuance in the future, an assessment by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) says.

The paper, titled A Retail Central Bank Digital Currency: Economic Considerations in the Singapore Context, looks at what a retail CBDC could look like in the city-state, exploring its potential implications for financial stability and monetary policy.

According to the paper, retail payments in Singapore are already competitive, efficient and cheap, and new initiatives are in the pipeline to introduce more innovation. Additionally, the soundness of the Singapore dollar and its dominance in the domestic economy make it unlikely for any foreign currency to emerge as a substitution. These are some of the reasons why Singapore is in no hurry to develop a retail CBDC, MAS says.

Nevertheless, a digital Singapore dollar could bring a number of benefits. These include enabling greater innovation in payments and payment-adjacent digital services, as well as providing a digital medium of exchange that’s safe, liquid, widely accepted and which better addresses users’ growing preference for digital channels.

Changing customer preferences and market shifts

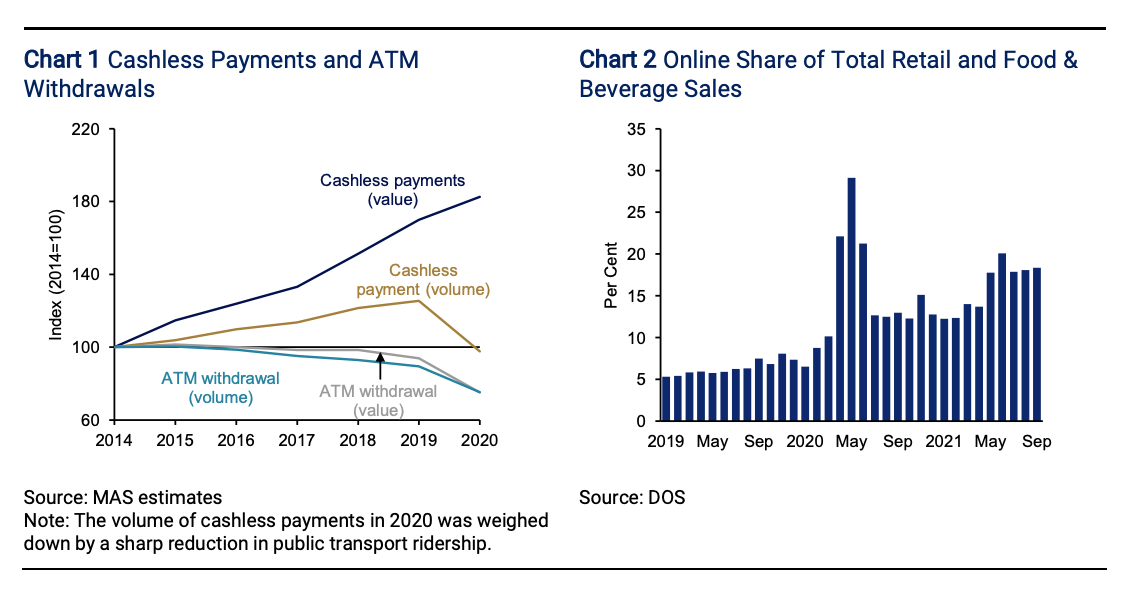

In Singapore, the use of cash has steadily declined over the years, while cashless, digital payments have risen sharply. This trend accelerated with COVID-19.

In 2020, total registrations by individuals and firms for the PayNow peer-to-peer (P2P) instant fund transfer service increased by around 50% to 4.9 million, while the value of PayNow and PayNow Corporate transactions tripled to S$38 billion.

In contrast, the use of cash for point-of-sale (POS) transactions fell to 26% in 2020, from 37% of in 2019.

Payment trends and e-commerce sales volumes, Source: Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), Nov 2021

At the same time, bigtechs are increasingly facilitating payments directly on their platforms, building off their large user bases and vibrant digital ecosystems to attract millions of users. Their entry into payments poses a number of risks, MAS says, including concerns over market concentration and monopolies.

Dominant firms could, for example, charge unjustifiably high fees for payment services to both end users and merchants. Digital monopolists could also engage in a range of undesirable rent-seeking behavior, such as unethical consumer targeting, the report says.

Laying the groundwork for a retail CBDC

Although MAS isn’t planning to launch a digital currency for the retail market any time soon, the central bank is nevertheless looking to lay the foundation should the nation decide to do so in the future.

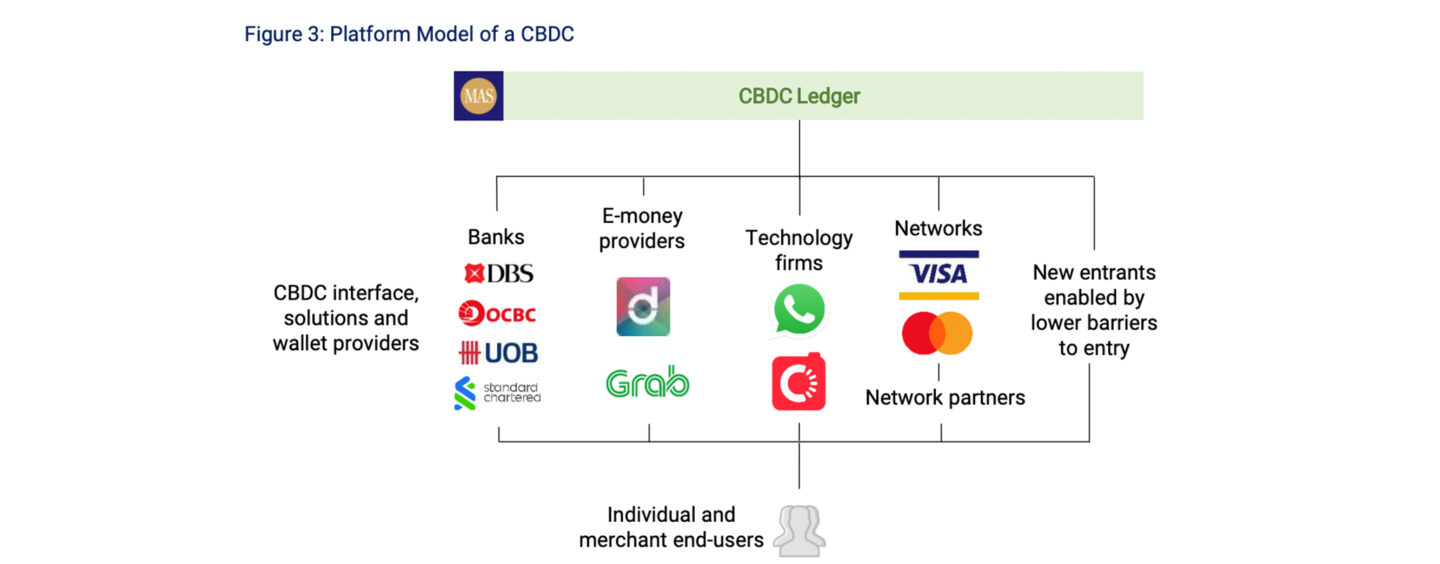

Through Project Orchid, MAS is working in close partnership with the private sector to build the technology infrastructure and competencies needed to introduce a retail CBDC system. Project Orchid will build on the findings from the Global CBDC Challenge, a startup competition focusing on innovations related to retail CBDCs.

Despite its work on retail CBDC, MAS says it remains “open to a range of possibilities for the future of money and payments,” adding that it will also be studying other emerging forms of digital money including privately-issued Singapore dollar-denominated stablecoins and synthetic CBDCs.

MAS’ work on a digital Singapore dollar comes at a time when central banks around the world are either actively considering or trialing CBDCs such as the digital euro, Bank of Japan’s digital yen and the People’s Bank of China’s e-CNY scheme.

Simultaneously, progresses are being made on linking up CBDCs. Project Dunbar, for example, seeks to develop prototypes for shared platforms that would enable international settlements with CBDCs. The project is led by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and includes involvement of MAS, the Reserve Bank of Australia, Bank Negara Malaysia and the South African Reserve Bank.