The Future of Cross-Border Transfers Could Be Central Bank-Backed Digital Currency

by Fintech News Singapore November 20, 2018As we slowly but surely move towards a global village into a reality, the overall value of cross-border payments is also expected to rise by 5.5% yearly, increasing from US$22 trillion in 2016 to US$30 trillion in 2022. Yet, according to a report published by KPMG , active correspondent bank numbers are at a slow decline.

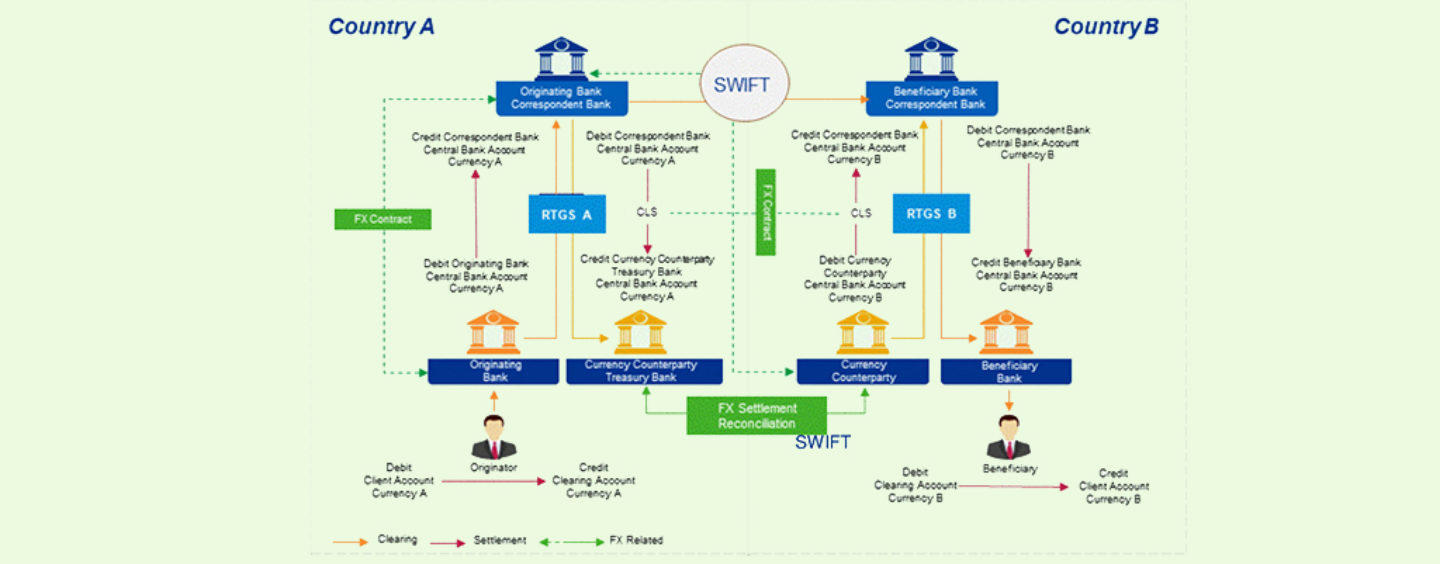

These factors are important to the development of cross-border money transfers, which even today are still expensive, slow, and lack transparency. Yet, because different nations come with their own individualised legacy systems, it has been a struggle not only to get involved countries onto the same platform, it has also been difficult to get everyone on board a similar structure.

The Challenges to solve are:

- Lack of a standardized payment status notification capability across the common payment messaging network used by banks

- Mismatch in operating hours of RTGS systems and commercial banks systems across different jurisdictions and time zones

- Lack of common, consistent payment standards (technical and operational) and regulatory requirements across jurisdictions

- Reliance on multiple intermediaries (with associated cost and complexity) for crossborder payments and settlements

- Challenges associated with legacy payments infrastructure across networks, central banks and commercial banks

Digital Currencies Under Consideration

Utilising digital currencies, whether they are on blockchain or not, could solve some of the problems outlined above. KPMG hypothesises that using digital currencies, specifically wholesale central bank digital currency (WCBDC) platform could address issues like service availability and payment visibility and that uses harmonized and data-rich messaging standards from inception can be more successful in delivering widespread change.

This could be one of the important utilities of a central bank-backed cryptocurrency as suggested by Christine Lagarde here.

But Implementation Will Not Be Simple

Unfortunately, the methods outlined come with its costs, which could be high for implementation in countries with less developed financial market infrastructures.

If costs are too prohibitive, then WCBDCs may not help with the problem of fragmentation slowing the current model we already use.

There’s also a concern that the creation of WCBDC tokens could impact money supply and monetary policy within a jurisdiciton, which means that central banks have to carefully consider what the tokens would mean for their individual nations.

Not to mention, the above benefits would only really occur as long as the model change comes with greater availability, wider access, interoperability and data-rich messaging standards, which may not necessarily be the case.

So what would likely happen is that while WCBDCs might eventually help cross-border interbank payments, programmes will probably start with a few participating countries at the beginning, with others only joining if the experiment proves fruitful. So nations joining right out of the gate will then have to ensure that frameworks and requirements they agree upon don’t create any further complexity and challenges for other nations that could participate in the future.

Despite this, both Bank of Canada and the Monetary Authority of Singapore have both explored the use of tokenised forms of central bank liabilities, with Bank of Canada running project Jasper, and Singapore running project Ubin respectively, though both projects’ explorations so far have been domestic.

Therefore,the models outlined below are still theoretical.

What WCBDC-Backed Cross-Border Payments Could Look Like

Model 1: Tokenising The Existing System

In the first model, banks in Country A and Country B both only hold WCBDCs of their respective countries. Bank C holds WCBDCs in wallets in both countries. So if a bank from Country A wants to remit money to a bank in Country B, it could remit money to the intermediary Bank C, and simultaenously, Bank C will remit money to the bank in Country B.

Alternately, the bank in Country A could remit money to the wallet that is jointly held by the central bank in Country B.

Therefore, this model would simply be the tokenisation of the existing correspondent banking model for cross-border transfers, though now with 24/7 operations through the design of a new platform.

For this model to truly challenge the status quo though, it requires broadened access to settlement accounts, which would enable entities, such as Bank C, to hold WCBDC wallets in different real time gross settlements (RTGS) systems.

Since this model still relies on correspondent banks though, many of the inherent problems that currently exist may still persist, though at least transactions will be quicker, and if on blockchain, more transparent.

Model 2: Allow Their WCBDCs to Circulate Outside of Country Borders

In this model, central banks from both Country A and Country B form an agreement that allows participating banks in both countries to hold and exchange WCBDCs issued by both central banks.

Participating banks can maintain WCBDC wallets for different currencies with the central banks of each participating country, and allow for payments and receipts of different WCBDCs as part of cross-border transactions with other banks.

The platforms for transfer of WCBDCs can be designed to operate 24/7, seven days a week, and still operate parallel to existing RTGS platforms so it can transact in WCBDCs between banks and central banks.

With WCBDCs that are circulating outside of a country’s jurisdiction though, this model would create an additional concern: impact of the creation of WCBDCs on monetary supply and policy when circulated in other countries. In addition, the liability framework for a participating central bank to hold another central bank’s WCBDC on their balance sheet intraday and potentially overnight would need to be established. Both considerations are significant.

Such a delicate policy challenge could impact a country’s willingness to join this model, and thus simply adding clutter to an already complicated system.

Countries would also need to agree on eligibility criteria for settlement account holders to get onto the new platform, as they can supersede RTGS systems of each country.

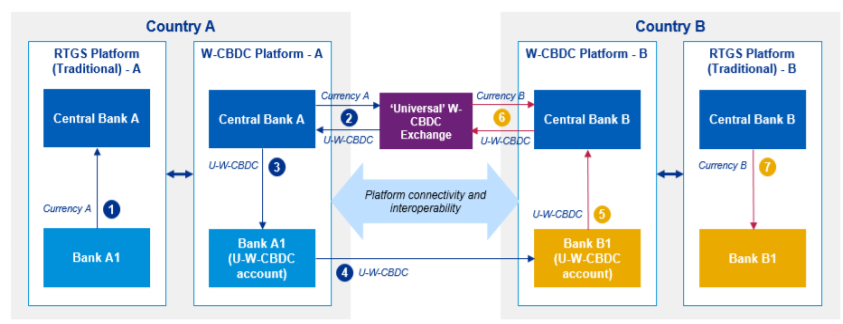

Model C: A Unified Digital Currency

Several countries, via their central banks, agree to create a universal WCBDC, which will be backed by a “basket of currencies issued by the participating central banks”. This universal WCBDC would be issued via a specially created exchange, and conversion of a country’s regular currency into the universal WCBDC would create an exchange rate between that currency and the universal WCBDC.

So all central networks involved will need to agree on a framework.

Banks that would like to settle peer-to-peer cross-border transactions would use these universal WCBDCs with other banks, and operate in parallel of the existing RTGS platforms to make transactions between banks and central banks.

While this method seemingly solves most of the issues outlined above in our current system, there will be significant policy questions that authorities need to address, while also potentially limiting its feasibility as a future-state model.

The report predicts that adoption of this model will also likely be slow, given it requires a huge change of the current system. Central banks would also have to further manage and monitor the supply of funds, cash, domestic RTGS and international universal WCBDCs. Frameworks will have to be developed to ensure that the universal WCBDCs have adquate collaterilasion with central banks in case of volatily intrday exchange rates.

The universal WCBDC could also be used other than transactions, and be subject to speculation and hoarding, which could impact price and utility of such a token.

Overall, the report finds that while a number of initiatives both planned and underway look to resolve pain points associated with cross-border payments, the majority of these are either too specific to a particular jurisdiction or a limited set of member banks, and are too focused on specific aspects of cross-border payments.

To us, this sounds like the beginning of most emerging sectors, and probably implies that the processes simply have not congealed into a unified standard that is adopted by the majority yet.

Therefore, the possibility of tokenising our current interbank cross-border transactions is still feasible. But the exploration of all three models reveal that it will require a huge mindset change in many central banks across the globe, especially considering the mistrust many have displayed towards cryptocurrencies and tokens so far.

For more information about the models explored, or other potential future cross-border transactions, you can read the full report here.