Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) represent a transformative development in the financial industry, as a growing number of countries rapidly progress from theoretical considerations to focused research and pilot programs. The compelling advantages of CBDCs have garnered the attention of even those nations initially unconvinced of their immediate necessity, prompting them to invest in the infrastructure needed for CBDC issuance.

The advent of CBDCs could have significant implications for monetary policy, according to a new working paper. While many central banks are exploring the benefits of CBDCs, few studies have examined their impact on monetary policy in depth.

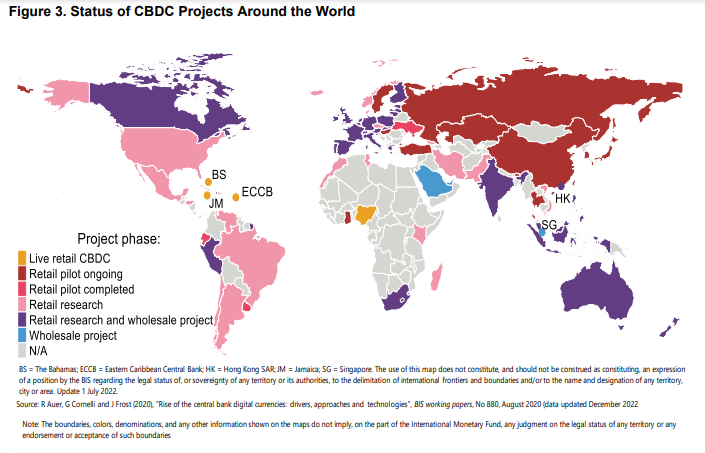

A number of countries including China, Australia, South Africa, India and Thailand are experimenting with, or have already tested hybrid CBDCs that merge both retail and wholesale functionalities. Meanwhile, other governments like the US, Canada, Japan and Indonesia are at different stages of exploration and development for their own CBDCs.

Although the exact timeline for widespread adoption remains uncertain, current trends indicate that CBDCs are poised to become a prevalent component of the global financial ecosystem, underscoring their potential to reshape monetary systems and drive economic growth in the coming years.

The working paper Monetary Policy Implications Central Bank Digital Currencies: Perspectives on Jurisdictions with Conventional and Islamic Banking Systems published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlights the characteristics of both retail and wholesale CBDCs (w-CBDCs) as well as the implications they could pose on monetary policy.

The Risks Associated with Poorly Designed CBDCs

To ensure the successful implementation of CBDCs, central banks must establish foundational principles that guide the design and operation of digital currencies. These principles should be aimed at promoting financial stability, enhancing payment system efficiency, and ensuring access to public money.

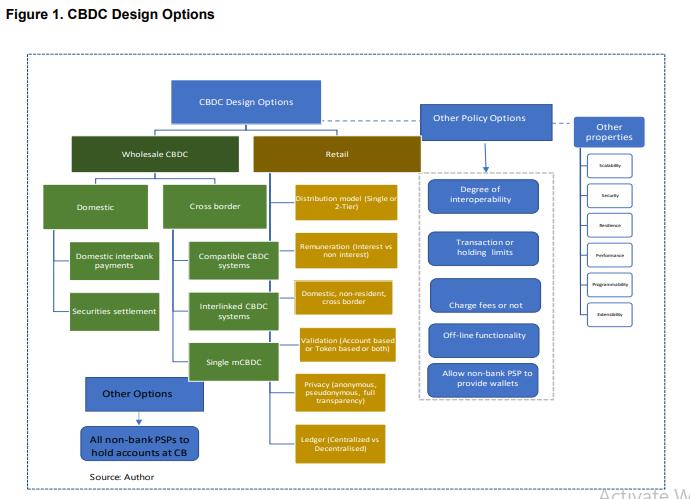

Source: Inutu Lukonga, Monetary Policy Implications Central Bank Digital Currencies: Perspectives on Jurisdictions with Conventional and Islamic Banking Systems, IMF

Poorly designed CBDCs could have unintended consequences on financial stability, monetary policy implementation, and payment systems. Therefore, understanding the potential risks and designing CBDCs that limit disruption is crucial.

To mitigate potential risks, the IMF argues that central banks should consider designs that limit disruptions to the financial status quo caused by CBDCs. One such design is the two-tiered unremunerated retail CBDC, which allows for controlled access to digital central bank money while preserving financial stability.

Two-tiered retail CBDCs involve the distribution of digital currencies through commercial banks, rather than direct access by the public. This design minimises the risk of deposit disintermediation, which occurs when the amount of funds being withdrawn overtakes the amounts being deposited, while at the same time maintaining the role of commercial banks in the financial system.

How CBDCs Will Impact Monetary Policy Implementation, Distribution

Retail CBDC refers to a central bank digital currency that is available for use by the general public and can be used for everyday transactions, whereas wholesale CBDC (w-CBDC) is designed for use by financial institutions and for large-scale interbank transactions.

Presently, adoption of retail CBDCs are still in its infancy, while w-CBDCs have yet to progress to any wide-scale adoption or even pilot or trial programmes. Two years after launch, the CBDC issued in the Bahamas accounts for less than 0.1% of currency in circulation, adoption of Nigeria’s e-Naira is at just 0.15%, and Jamaica’s JAM-DEX digital currency uptake is reportedly slowly rising.

Advanced pilots run by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) show that the e-CNY digital currency represents around 0.13% of the total currency in circulation by end-December 2022. While sluggish now, in future the theoretical shift in preferences between deposits and CBDCs will have significant implications for the banking sector and the effectiveness of the monetary policy in adoptive countries.

As more individuals and businesses choose to hold CBDCs over traditional bank deposits, banks may face reduced funding sources, potentially leading to changes in the composition and cost of bank lending. This, in turn, can affect monetary policy transmission through the credit channel as banks adjust their lending practices in response to the altered funding environment.

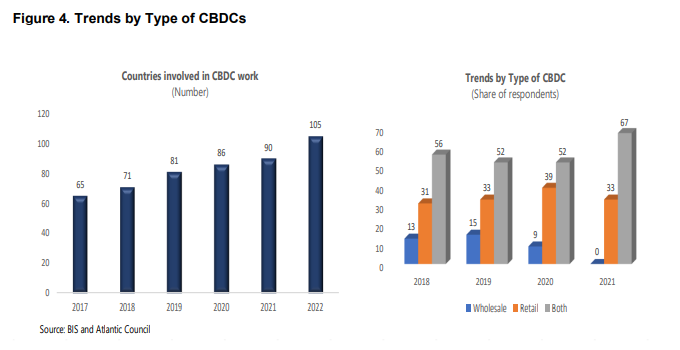

Source: Bank of International Settlements and Atlantic Council, via Inutu Lukonga, Monetary Policy Implications Central Bank Digital Currencies: Perspectives on Jurisdictions with Conventional and Islamic Banking Systems, IMF

Furthermore, the widespread adoption of CBDCs may alter the role of commercial banks in the monetary policy transmission process, as central banks gain the ability to directly influence the public’s spending and saving behaviour through CBDC interest rates. Consequently, central banks could achieve their policy objectives more directly, bypassing the need for intermediation by commercial banks.

However, the introduction of CBDCs also presents challenges to monetary policy implementation. A rapid switch from bank deposits to CBDCs could result in disintermediation and liquidity risks for the banking sector, potentially destabilising the financial system.

To avoid these risks from the outset, central banks must carefully design and manage the issuance of CBDCs, ensuring that the transition to this new form of money remains smooth and does not inadvertently hinder the effectiveness of the monetary policy.

Future Cross-border Application of CBDCs

As they become more mainstream, cross-border usage of CBDCs can impact monetary policy in both the countries issuing the CBDCs and those receiving them.

The issuing countries may face difficulties in controlling monetary aggregates if there is high foreign demand for their CBDCs. This increase in currency outside their borders may cause capital inflows and potentially lead to appreciation pressures on exchange rates, affecting inflation and monetary policy implementation depending on the weight of imports in the consumer basket.

Recipient countries may see a decrease in control over domestic liquidity as CBDC substitution increases, states the IMF. Although CBDC substitution is similar to traditional “dollarisation” experienced in countries with high inflation and exchange rate volatility, the accessibility and ease of reserve asset CBDCs may speed up and expand the substitution process. Greater currency substitution due to foreign CBDC usage could also negatively impact seigniorage (the profit a country makes from issuing currency, after minusing the production costs) for the recipient country.

Source: Inutu Lukonga, Monetary Policy Implications Central Bank Digital Currencies: Perspectives on Jurisdictions with Conventional and Islamic Banking Systems, IMF

Both the issuing and recipient countries may experience challenges in rapid cross-border settlement. Increased speed in cross-border payments could result in higher capital flow volatility, making it more difficult for domestic monetary authorities to manage exchange rates and monetary policy.

The use of w-CBDCs for cross-border settlement will grow, and could lead to increased and potentially more volatile intraday demand for central bank money. Non-resident banks’ access to intraday w-CBDC could increase demand for overnight reserves held by resident banks acting as correspondents, potentially influencing liquidity management by market participants, the price of liquidity, and the transmission of monetary policy.

The IMF working paper outlines complex potential challenges that may become prevalent as uptake of retail and w-CBDCs increase, including those impacting regions with a sizable Islamic banking sector. But the paper is also quick to note that much of the analyses are “still largely conceptual and tentative”, owing largely to the fact empirical data is still insufficient as only a few countries have issued CBDCs thus far, and for a relatively short period of time.

But for central banks looking to avoid some of the foreseeable pitfalls of rolling out their CBDC, some can be sidestepped by staying aware of the conceptual challenges highlighted by the IMF.