Economies worldwide are increasingly considering the viability of a digitised national currency, most commonly referred to now as a Central Bank Digital Currency, or CBDC. Eleven countries have already launched their CBDCs, but none in Asia yet.

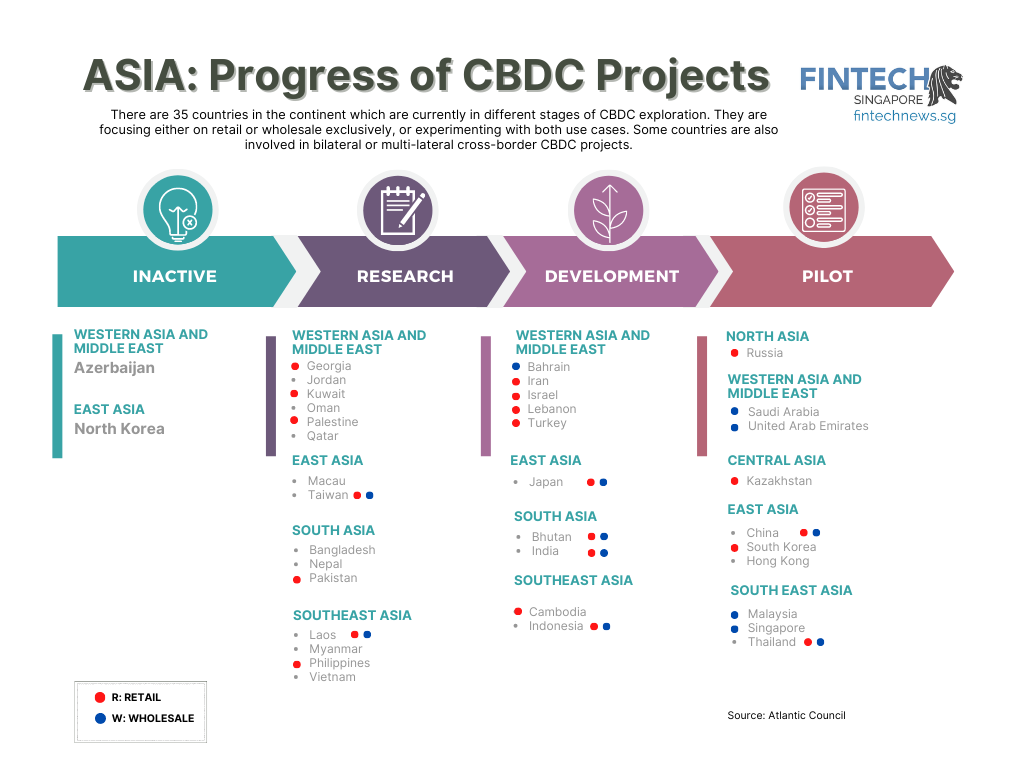

There are currently 35 countries in Asia that are in different stages – either research, development, or pilot – of CBDC exploration, according to the American think tank Atlantic Council which tracks the digital currency status worldwide.

The closest to a full-scale launch is likely China next year, where it was the first to introduce the digital yuan, or e-CNY, in August 2020.

Why the growing interest in the CBDC?

Here are the basics. It is the digital version of a country’s legal tender backed and issued by its central bank. Since it is literally just the digital version, its value is the same as the physical paper notes. For example, 100 e-CNY is equal to 100 yuan. They can be held in an account with the central bank or as electronic tokens in digital wallets, mobile devices, and prepaid cards.

There are two known use cases for CBDCs. First, retail is denoted by CBDC-R, which is involved in transactions by the general public. The second is wholesale, wCBDC, used in bank-to-bank transactions and settlements by financial institutions.

Countries can design their CBDC for both use cases, like China and Thailand, or start with either, such as South Korea and Russia, piloting for retail use; meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and Singapore are testing for wholesale only.

Asia is rife with CBDC activities

Asia is rife with CBDC activities as the region, home to many emerging markets, is quick to adopt new technology and keen to extract more benefits from innovations. CBDCs make use of blockchain technology, like cryptocurrencies, but the country’s monetary sovereignty is still preserved since each country’s respective central bank issues them.

Due to its decentralized nature, it doesn’t have to be bogged down by the legacy system, such as the US dollar financial channels, which makes a country’s economy vulnerable to changes in US monetary or political policies like trade sanctions.

Aside from that, expanding financial inclusion is a core objective behind the increasing interest in CDBCs. Going digital can facilitate transactions at home and across the border, as experienced during the rapid digitalization and further penetration of mobile and internet access in the initial two years of the covid-19 pandemic.

The CBDC is a part of the continuing enhancements in modern monetary transactions, including real-time settlement and lower transaction costs.

In fact, the UN Sustainable Development Goal for 2030 is committed to reducing transaction costs of migrant remittances to less than three percent and eliminating remittance corridors with prices higher than five percent.

“Migrant workers sending US$200 back home on a banking rail have to pay more than US$18 (six percent), which is more than double the UN Sustainable Development Goal target, according to the World Bank.

As part of ongoing inclusive interoperable technologies implementations, CBDCs need to play a key role in further reducing cross-border settlement costs to reach the three percent SDG goal,” said Nick Drury, director of Mojaloop CBDC Center of Excellence in Singapore, recently.

Asia has yet to launch CBDC fully

While the technology is promising, there are concerns – from infrastructure, cybersecurity, and privacy to combating fraud, terrorism funding, and money laundering – which still need to be addressed.

This probably explains why no country in Asia has yet to launch its CBDC fully. So far, there are 15 countries still doing research on CBDCs, 10 in the development stage and 10 in the pilot phase, according to the Atlantic Council tracker. Out of the (almost) 11 ASEAN countries, only Brunei and Timor-Leste have yet to make a known plan for CBDC.

Last Wednesday, Indonesia’s central bank released a whitepaper detailing its plans for its CBDC Project Garuda, the national initiative to develop a digital rupiah. This will be carried out in three stages, with the wholesale digital rupiah being examined first.

Those doing CBDC pilot schemes include Russia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kazakhstan, China, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand.

The Reserve Bank of India has started its first wCDBC pilot for e-rupee this month and intends to begin an experiment for retail uses with five banks this December. The Bank of Japan will begin a trial of using digital yen with the country’s three big banks and regional banks next year.

Cross-border CBDC projects in Asia

Furthermore, some countries in Asia have completed or are participating in cross-border CBDC projects. The mCBDC Bridge sees a collaboration between the BIS Innovation Hub Hong Kong Centre, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Bank of Thailand, the Digital Currency Institute of the People’s Bank of China, and the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates on a multi-CBDC platform.

The Bank of Japan has worked on Project Stella with the European Central Bank, and the central banks of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have Project Aber.

Singapore, meanwhile, has more than a few wholesale CBDC projects under its belt. It has Project Dunbar with Australia, Malaysia, and South Africa; Project Jasper with Canada and the UK; Onyx/Multiple wCBDC with France; and Project Cedar Phase II x Ubin+ between the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and the New York Innovation Center of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

MAS will also be experimenting with automated market makers for foreign exchange using wCBDC with Banque of France and Swiss National Bank in Project Mariana.